DEMOCRATIZATION ---- GENERAL STUDIES FORM V & VI.

INTRODUCTION

| This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2013) |

Voting is an important part of the democratic process.

Contents

Causes of democratization

Percentage of countries in each category over time, from Freedom House's 1973 through 2013 reports.

Free (90) Partly Free (58) Not Free (47)

- Wealth. A higher GDP/capita correlates with democracy and while some claim the wealthiest democracies have never been observed to fall into authoritarianism, Hitler would be an obvious counter-example that would render the claim a truism.[1] There is also the general observation that democracy was very rare before the industrial revolution. Empirical research thus lead many to believe that economic development either increases chances for a transition to democracy (modernization theory), or helps newly established democracies consolidate.[1] Some campaigners for democracy even believe that as economic development progresses, democratization will become inevitable. However, the debate about whether democracy is a consequence of wealth, a cause of it, or both processes are unrelated, is far from conclusion.

- Education. Wealth also correlates with education, though their effects on democratic consolidation seem to be independent.[1] A poorly educated and illiterate population may elect populist politicians who soon abandon democracy and become dictators even if there have been free elections.

- The resource curse theory suggests that countries with abundant natural resources, such as oil, often fail to democratize because the elite can live off the natural resources rather than depend on popular support for tax revenues. On the other hand, elites who invested in the physical capital rather than in land or oil, fear that their investment can be easily damaged in case of a revolution. Consequently, they would rather make concessions and democratize than risk a violent clash with the opposition.[2]

- Market economy. Some claim that democracy and market economy are intrinsically linked. This belief generally centers on the idea that democracy and market economy are simply two different aspects of freedom. A widespread market economy culture may encourage norms such as individualism, negotiations, compromise, respect for the law, and equality before the law.[3] These are seen as supportive for democratization.

- Social equality. Acemoglu and Robinson argued that the relationship between social equality and democratic transition is complicated: People have less incentive to revolt in an egalitarian society (for example, Singapore), so the likelihood of democratization is lower. In a highly unequal society (for example, South Africa under Apartheid), the redistribution of wealth and power in a democracy would be so harmful to elites that these would do everything to prevent democratization. Democratization is more likely to emerge somewhere in the middle, in the countries, whose elites offer concessions because (1) they consider the threat of a revolution credible and (2) the cost of the concessions is not too high.[2] This expectation is in line with the empirical research showing that democracy is more stable in egalitarian societies.[1]

- Middle class. According to some models,[2] the existence of a substantial body of citizens who are of intermediate wealth can exert a stabilizing influence, allowing democracy to flourish. This is usually explained by saying that while the upper classes may want political power to preserve their position, and the lower classes may want it to lift themselves up, the middle class balances these extreme positions.

- Civil society. A healthy civil society (NGOs, unions, academia, human rights organizations) are considered by some theorists to be important for democratization, as they give people a unity and a common purpose, and a social network through which to organize and challenge the power of the state hierarchy. Involvement in civic associations also prepares citizens for their future political participation in a democratic regime.[4] Finally, horizontally organized social networks build trust among people and trust is essential for functioning of democratic institutions.[4]

- Civic culture. In The Civic Culture and The Civic Culture Revisited, Gabriel A. Almond and Sidney Verba (editors) conducted a comprehensive study of civic cultures. The main findings is that a certain civic culture is necessary for the survival of democracy. This study truly challenged the common thought that cultures can preserve their uniqueness and practices and still remain democratic.

- Culture. It is claimed by some that certain cultures are simply more conductive to democratic values than others. This view is likely to be ethnocentric. Typically, it is Western culture which is cited as "best suited" to democracy, with other cultures portrayed as containing values which make democracy difficult or undesirable. This argument is sometimes used by undemocratic regimes to justify their failure to implement democratic reforms. Today, however, there are many non-Western democracies. Examples include India, Japan, Indonesia, Namibia, Botswana, Taiwan, and South Korea.

- Human Empowerment and Emancipative Values. In Modernization, Cultural Change and Democracy,[5] Ronald Inglehart and Christian Welzel explain democratization as the result of a broader process of human development,[6] which empowers ordinary people in a three-step sequence. First, modernization gives more resources into the hands of people, which empowers capability-wise, enabling people to practice freedom. This tends to give rise to emancipative values that emphasize freedom of expression and equality of opportunities. These values empower people motivation-wise in making them willing to practice freedom. Democratization occurs as the third stage of empowerment: it empowers people legally in entitling them to practice freedom.[7] In this context, the rise of emancipative values has been shown to be the strongest factor of all in both giving rise to new democracies and sustaining old democracies.[8] Specifically, it has been shown that the effects of modernization and other structural factors on democratization are mediated by these factors tendencies to promote or hinder the rise of emancipative values.[9] Further evidence suggests that emancipative values motivate people to engage in elite-challenging collective actions that aim at democratic achievements, either to sustain and improve democracy when it is granted or to establish it when it is denied.[10] A compact summary and update of this "emancipatory theory of democracy" can be found in Freedom Rising.[11]

- Homogeneous population. Some believe that a country which is deeply divided, whether by ethnic group, religion, or language, have difficulty establishing a working democracy.[12] The basis of this theory is that the different components of the country will be more interested in advancing their own position than in sharing power with each other. India is one prominent example of a nation being democratic despite its great heterogeneity.

- Previous experience with democracy. According to some theorists, the presence or absence of democracy in a country's past can have a significant effect on its later dealings with democracy. Some argue, for example, that it is very difficult (or even impossible) for democracy to be implemented immediately in a country that has no prior experience with it. Instead, they say, democracy must evolve gradually. Others, however, say that past experiences with democracy can actually be bad for democratization — a country, such as Pakistan, in which democracy has previously failed may be less willing or able to go down the same path again.

- Foreign intervention. Democracies have often been imposed by military intervention, for example in Japan and Germany after WWII.[13][14] In other cases, decolonization sometimes facilitated the establishment of democracies that were soon replaced by authoritarian regimes. For example, in the United States South after the Civil War, former slaves were disenfranchised by Jim Crow laws after the Reconstruction Era of the United States; after many decades, U.S. democracy was re-established by civic associations (the African American civil rights movement) and an outside military (the U.S. military).

- Age distribution. Countries which have a higher degree of elderly people seems to be able to maintain democracy, when it has evolved once, according to a thesis brought forward by Richard P. Concotta in this article[15] in Foreign Policy. When the young population (defined as people aged 29 and under) is less than 40%, a democracy is more safe, according to this research.

Transitions

Democracy development has often been slow, violent, and marked by frequent reversals.[16]Historical Cases

In Great Britain, the English Civil War (1642–1651) was fought between the King and an oligarchic but elected Parliament. The Protectorate and the English Restoration restored more autocratic rule. The Glorious Revolution (1688) established a strong Parliament. The Bill of Rights 1689 (which is still in effect) codified certain rights and liberties for subjects and set out the rights of Parliament, rules for freedom of speech in Parliament and limited the power of the monarch, ensuring that, unlike much of the rest of Europe, royal absolutism would not prevail.[17] Only with the Representation of the People Act 1884 did a majority of the males get the vote.The American Revolution (1765–1783) created the United States. In many fields, it was a success ideologically in the sense that a relatively true republic was established that never had a single dictator, but slavery was only abolished with the American Civil War (1861–1865), and Civil Rights given to African-Americans became achieved in the 1960s.

The French Revolution (1789) briefly allowed a wide franchise. The French Revolutionary Wars and the Napoleonic Wars lasted for more than twenty years. The French Directory was more oligarchic. The First French Empire and the Bourbon Restoration restored more autocratic rule. The Second French Republic had universal male suffrage but was followed by the Second French Empire. The Franco-Prussian War (1870–71) resulted in the French Third Republic.

The German Empire was created in 1871. It was followed by the Weimar Republic after World War I. Nazi Germany restored autocratic rule before the defeat in World War II .

The Kingdom of Italy, after the unification of Italy in 1861, was a constitutional monarchy with the King having considerable powers. Italian fascism created a dictatorship after the World War I. World War II resulted in the Italian Republic.

The Meiji period, after 1868, started the modernization of Japan. Limited democratic reforms were introduced. The Taishō period (1912–1926) saw more reforms. The beginning of the Shōwa period reversed this until the end of the World War II.

Since 1972

According to a study by Freedom House, in 67 countries where dictatorships have fallen since 1972, nonviolent civic resistance was a strong influence over 70 percent of the time. In these transitions,"changes were catalyzed not through foreign invasion, and only rarely through armed revolt or voluntary elite-driven reforms, but overwhelmingly by democratic civil society organizations utilizing nonviolent action and other forms of civil resistance, such as strikes, boycotts, civil disobedience, and mass protests."[18]

Indicators of democratization

One influential survey in democratization is that of Freedom House, which arose during the Cold War. The Freedom House, today an institution and a think tank, stands as one of the most comprehensive "freedom measures" nationally and internationally and by extension a measure of democratization. Freedom House categorizes all countries of the world according to a seven point value system with over 200 questions on the survey and multiple survey representatives in various parts of every nation. The total raw points of every country places the country in one of three categories: Free, Partly Free, or not Free.One study simultaneously examining the relationship between market economy (measured with one Index of Economic Freedom), economic development (measured with GDP/capita), and political freedom (measured with the Freedom House index) found that high economic freedom increases GDP/capita and a high GDP/capita increases economic freedom. A high GDP/capita also increases political freedom but political freedom did not increase GDP/capita. There was no direct relationship either way between economic freedom and political freedom if keeping GDP/capita constant.[19]

Views on democratization

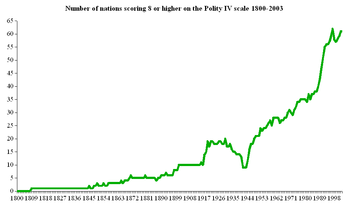

Francis Fukuyama wrote another classic in democratization studies entitled The End of History and the Last Man which spoke of the rise of liberal democracy as the final form of human government. However it has been argued that the expansion of liberal economic reforms has had mixed effects on democratization. In many ways, it is argued, democratic institutions have been constrained or "disciplined" in order to satisfy international capital markets or to facilitate the global flow of trade.[20]Samuel P. Huntington wrote The Third Wave, partly as response to Fukuyama, defining a global democratization trend in the world post WWII. Huntington defined three waves of democratization that have taken place in history.[21] The first one brought democracy to Western Europe and Northern America in the 19th century. It was followed by a rise of dictatorships during the Interwar period. The second wave began after World War II, but lost steam between 1962 and the mid-1970s. The latest wave began in 1974 and is still ongoing. Democratization of Latin America and the former Eastern Bloc is part of this third wave.

A very good example of a region which passed through all the three waves of democratization is the Middle East. During the 15th century it was a part of the Ottoman empire. In the 19th century, "when the empire finally collapsed [...] towards the end of the First World War, the Western armies finally moved in and occupied the region".[22] This was an act of both European expansion and state-building in order to democratize the region. However, what Posusney and Angrist argue is that, "the ethnic divisions [...] are [those that are] complicating the U.S. effort to democratize Iraq". This raises interesting questions about the role of combined foreign and domestic factors in the process of democratization. In addition, Edward Said labels as 'orientalist' the predominantly Western perception of "intrinsic incompatibility between democratic values and Islam". Moreover, he states that "the Middle East and North Africa lack the prerequisites of democratization".[23]

Fareed Zakaria has examined the security interests benefited from democracy promotion, pointing out the link between levels of democracy in a country and of terrorist activity. Though it is accepted that poverty in the Muslim world has been a leading contributor to the rise of terrorism, Zakaria has noted that the primary terrorists involved in the 9/11 attacks were among the upper and upper-middle classes. Zakaria has suggested that the society in which Al-Qaeda terrorists lived provided easy money, and therefore there existed little incentive to modernize economically or politically.[24] With little opportunity to express themselves in the political sphere, scores of young Arab men were "invited to participate"[25] through another avenue: the culture of Islamic fundamentalism. The rise of Islamic fundamentalism and its violent expression on September 11, 2001 illustrates an inherent need to express oneself politically, and a democratic government or one with democratic aspects (such as political openness) is quite necessary to provide a forum for political expression.

Democratization in other contexts

Although democratization is most often thought of in the context of national or regional politics, the term can also be applied to:International bodies

- International bodies (e.g. the United Nations) where there is an ongoing call for reform and altered voting structures and voting systems.

Corporations

It can also be applied in corporations where the traditional power structure was top-down direction and the boss-knows-best (even a "Pointy-Haired Boss"); This is quite different from consultation, empowerment (of lower levels) and a diffusion of decision making (power) throughout the firm, as advocated by workplace democracy movements.The Internet

The loose anarchistic structure of the Internet Engineering Task Force and the Internet itself have inspired some groups to call for more democratization of how domain names are held, upheld, and lost. They note that the Domain Name System under ICANN is the least democratic and most centralized part of the Internet, using a simple model of first-come-first-served to the names of things. Ralph Nader called this "corporatization of the dictionary."Knowledge

The democratization of knowledge is the spread of knowledge among common people, in contrast to knowledge being controlled by elite groups.Design

The trend that products from well-known designers are becoming cheaper and more available to masses of consumers. Also, the trend of companies sourcing design decisions from end users.[26]See also

- Third Wave Democracy

- Chilean transition to democracy

- Democratisation in Hong Kong

- Democratisation in the Soviet Union

- Color revolution

- Democracy activists

- Democracy in the Middle East

- Democratic peace theory

- Democracy promotion

- Metapolitefsi

- Nation-building

- Nonviolent revolution

- Portuguese transition to democracy

- Spanish transition to democracy

- Transitional justice

- Transitology

References

- Przeworski, Adam; et al. (2000). Democracy and Development: Political Institutions and Well-Being in the World, 1950-1990. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Acemoglu, Daron; James A. Robinson (2006). Economic Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Mousseau, Michael. (2000). Market Prosperity, Democratic Consolidation, and Democratic Peace. Journal of Conflict Resolution 44(4):472-507.

- Putnam, Robert D.; et al. (1993). Making Democracy Work: Civic Traditions in Modern Italy. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- * Inglehart, Ronald & Welzel, Christian (2005), Modernization, Cultural Change and Democracy: The Human Development Sequence, New York: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 9780521846950.

- Inglehart, Ronald; Klingemann, Hans-Dieter; Welzel, Christian (2003), "The Theory of Human Development: A Cross-Cultural Analysis", European Journal of Political Research 42 (3): 341–380, doi:10.1111/1475-6765.00086.

- Christian Welzel & Ronald Inglehart (2008): "The Role of Ordinary people in Democratization." Journal of Democracy 19: 126-40

- * Welzel, Christian (2006), "Democratization as an Emancipative Process", European Journal of Political Research 45 (6): 871–896, doi:10.1111/j.1475-6765.2006.00637.x.

- Christian Welzel (2007): "Are Levels of Democracy Affected by Mass Attitudes? Testing Sustainment and Attainment Effects on Democracy" International Political Science Review 28: 397-24

- Christian Welzel & Hans-Dieter Klingemann (2008). "Evidencing and Explaining Democratic Congruence: The Perspective of 'Substantive' Democracy." World Values Research 1:57-90

- * Welzel, Christian (2013), Freedom Rising: Human Empowerment and the Quest for Emancipation, New York: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 9781107664838.

- Marsha Pripstein Posusney. Authoritarianism in the Middle East: Regimes and Resistance. ed. by Marsha Pripstein Posusney and Michele Penner Angrist (Lynne Rienner Publishers Inc., USA, 2005)

- Therborn, Göran (1977). "The rule of capital and the rise of democracy: Capital and suffrage (cover title)". New Left Review. I 103 (The advent of bourgeois democracy): 3–41.

- The Independent

- Foreignpolicy.com

- Journal of Democracy

- "Rise of Parliament". The National Archives. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

- Study: Nonviolent Civic Resistance Key Factor in Building Durable Democracies, May 24, 2005

- Ken Farr, Richard A. Lord, and J. Larry Wolfenbarger (1998). "Economic Freedom, Political Freedom, and Economic Well-Being: A Causality Analysis". Cato Journal 18 (2): 247–262. [1]

- Roberts, Alasdair S.,Empowerment or Discipline? Two Logics of Governmental Reform (December 23, 2008). Available at http://ssrn.com/abstract=1319792 SSRN.com

- Huntington, Samuel P. (1991). Democratization in the Late 20th century. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

- Simon, Bromley. Rethinking Middle East Politics: State Formation and Development. (Polity Press, Cambridge, 1994)

- ed by Marsha, Pripstein Posusney and Michele, Penner Angrist. Authoritarianism in the Middle East: Regimes and Resistance. (Lynne Rienner Publishers, Inc., USA, 2005)

- Fareed Zakaria, The Future of Freedom: Illiberal Democracy at Home and Abroad, W.W. Norton & Co., 2007, 138.

- Fareed Zakaria, The Future of Freedom: Illiberal Democracy at Home and Abroad, W.W. Norton & Co., 2007.

- Harry (2007). The Democratization of Design

Further reading

- Thomas Carothers. Aiding Democracy Abroad: The Learning Curve. 1999. Washington, DC: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

- Josep M. Colomer. Strategic Transitions. 2000. Baltimore, Md: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Daniele Conversi. ‘Demo-skepticism and genocide’, Political Science Review, September 2006, Vol 4, issue 3, pp. 247–262

- Haerpfer, Christian; Bernhagen, Patrick; Inglehart, Ronald & Welzel, Christian (2009), Democratization, Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 9780199233021.

- Inglehart, Ronald & Welzel, Christian (2005), Modernization, Cultural Change and Democracy: The Human Development Sequence, New York: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 9780521846950.

- Frederic C. Schaffer. Democracy in Translation: Understanding Politics in an Unfamiliar Culture. 1998. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Fareed Zakaria. The Future of Freedom: Illiberal Democracy at Home and Abroad. 2003. New York: W.W. Norton.

- Christian Welzel. Freedom Rising: Human Empowerment and the Quest for Emancipation. 2013. New York: Cambridge University Press (ISBN 978-1-107-66483-8).

External links

| Look up democratization in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

|

||

|

||