AN ONLINE PLATFORM THAT PROVIDES EDUCATIONAL CONTENT,SYLLABUSES, STUDY NOTES/ MATERIALS ,PAST PAPERS, QUESTIONS & ANSWERS FOR THE STUDENTS,FORM I--VI ,RESITTERS,QT, ADULT LEARNERS, COLLEGE STUDENTS, PUPILS, TEACHERS, PARENTS,TEACHERS OF THE UNITED REPUBLIC OF TANZANIA AND WORLDWIDE.YOU ARE WELCOME TO SHARE YOUR KNOWLEDGE AND IDEAS.ENJOY MASATU BLOG.YOU CAN MAKE A DIFFERENCE.YOU CAN ACHIEVE EXCELLENCE. "LEARN.REVISE.DISCUSS".Anytime, Anywhere.

- HOME

- UTAKUZAJE UWEZO WAKO WA LUGHA ?

- MBINU ZA KUSOMA NA KUFAULU MITIHANI

- HOW TO IMPROVE YOUR MEMORY

- ONLINE LEARNING & DISTANCE LEARNING ( E--LEA...

- O-LEVEL & A--LEVEL SYLLABUS

- FORM FOUR ( F 4 )--SUBJECTS---TANZANIA

- FORM TWO ( F 2 )--SUBJECTS---TANZANIA

- FORM ONE ( F 1 )-- SUBJECTS---TANZANIA

- FORM FIVE( F 5 ) AND SIX ( F 6 )--SUBJECTS ---TANZANIA

- FORM THREE ( F 3 ) SUBJECTS----TANZANIA

- STANDARD 1 & 2 SUBJECTS / MASOMO YA DARASA 1 & 2-...

- STANDARD 3 & 4 SUBJECTS / MASOMO YA DARASA 3 & 4...

- STANDARD 5, 6 & 7 SUBJECTS / MASOMO YA DARASA...

Wednesday, October 29, 2014

Saturday, October 25, 2014

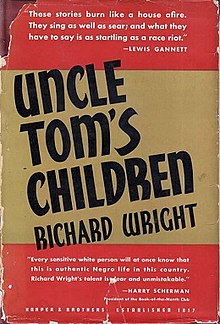

Uncle Tom"s Children by Richard Wright.

024: LITERATURE IN ENGLISH

NOVELS

Uncle Tom's Children is a

collection of short stories by African American author Richard Wright,

also the author of Black Boy, Native Son, and The

Outsider. Uncle Tom's Children includes four short

stories and was successful when it was first published in 1938. In 1940,

Harper reissued the volume as Uncle Tom's Children: Five Long Stories,

incorporating "Bright and Morning Star" as well as placing "The

Ethics of Living Jim Crow" as the text's introduction. The Harper

Perennial edition of Wright's novel Black Boy, under the heading 'Books by Richard Wright',

misprints "Uncle Tom's Children" as "Uncle Tom's Cabin".

Plot

The Ethics of

Living Jim Crow

"The Ethics of Living Jim

Crow" describes Wright's own experiences growing up. The essay starts with

his first encounter with racism, when his attempt to play a war game with white

children turns ugly, and follows his experiences with the problems of being

black in the South through his adolescence and adulthood. It describes his

experience of prejudice at his first job. While working at an optical factory,

his white fellow employees bully and eventually beat him for wanting to learn

job skills that could allow him to advance. Wright also discusses suffering

attacks by white youths and explores the many hypocrisies of white prejudice

against blacks. These include black men being allowed to work around naked

white prostitutes while having to pretend they do not exist. Whites have

exploitative sex with black maids, and yet any sexual relations between a black

man and a white woman, even a prostitute, is cause for castration or death.

Wright also delves into the more subtle humiliations inherent in the Jim Crow

system, such as being unable to say "thank you," to a white man, lest

he take it as a statement of equality.

Big Boy Leaves

Home

Big Boy was chosen to be the leader of

his friends. One day, Big Boy and friends Bobo, Lester, and Buck decide to go

swimming in a restricted area. They take off their clothes and proceed to play

in the water. Soon, a white woman comes upon them and the boys are unable to

get their clothes without being seen. After reacting to the boys with shock and

disgust, she calls for "Jim". Jim quickly appears and, feeling

threatened, proceeds to kill Lester and Buck. After a short struggle between

Big Boy and Jim, Big Boy takes control of the rifle and shoots Jim, seemingly

killing him. The remaining two members of the group quickly gather their

clothes and flee the scene. The story moves with Big Boy as he makes his way

back home. He relates the story to his family. All the while, Big Boy is

terrified that the white people will form a mob and lynch him. The family has

an acquaintance who drives a truck and can help Big Boy escape. Big Boy is sent

off with some food while he waits for the acquaintance to leave with the truck

at 6:00 AM the next morning. As he finds a place to settle for a while, he

overhears some white men discussing the search situation and learns that

they've captured Bobo, the other surviving boy of the original group of four.

Bobo is burned at the stake. Later, the acquaintance, Will, finds Big Boy and

they head off in the truck. The story ends in bittersweet fashion as Big Boy

thinks about the slaughter of his friends in the new sunny day.

Down by the

Riverside

"Down by the Riverside" takes

place during a major flood. Its main character, a farmer named Mann, must get

his family to safety in the hills, but he does not have a boat. In addition,

his wife, Lulu, has been in labor for several days but cannot deliver the baby.

Mann must get her to a hospital - the Red Cross hospital. He has sent his

cousin Bob to sell a donkey and use the money to buy a boat, but Bob returns

with only fifteen dollars from the donkey and a stolen boat. Mann must take the

boat through town to the hospital, even though Bob advises against this, since

the boat is very recognizable. Rowing his family, including Lulu, Peewee, his

son and Grannie, Lulu's mother, in this white boat, Mann calls for help at the

first house he reaches. This house is the home of the boat's white owner,

Heartfield, who immediately begins shooting. Mann, who has brought his gun,

returns fire and kills the man, while the man's family witnesses the act from

the windows of the house.

Mann rows on to the Red Cross hospital

but is too late; Lulu and the undelivered baby have died. Soldiers take away

Grannie and Peewee to safety in the hills, and Mann is conscripted to work on

the failing levee. However, the levee breaks, and Mann must return to the hospital,

where he smashes a hole in the ceiling at the direction of a colonel - who then

directs Mann to find him once everything's over saying he'll help Mann if he

can - allowing the hospital to be evacuated. Mann and a young black boy,

Brinkley, are told to rescue a family at the edge of town, who turn out to be

the Heartfields. Inside the house, Heartfield's son recognizes Mann as his

father's killer and Mann raises his axe thinking to kill the children &

their mother but is stopped when the house shifts in the rising flood waters.

Despite his terror that he might be fingered as Heartfield's murderer and

accordingly facing the possibility of a brutal and torturous death, Mann takes

the boy, the boy's sister and his mother to "the hills" and safety.

There, Mann tries to blend with "his people", hoping he might find

his family, until the white boy identifies Mann as the killer of his father.

Armed soldiers take Mann away after tribunal with the general and then the

colonel he'd helped at the Red Cross. Knowing he's doomed and vowing to

"die fo they kill [him]" Mann runs and the soldiers shoot him dead by

the river's edge.

Long Black Song

"Long Black Song" takes place

on a solitary farm, where a young black woman, Sarah, waits for her husband,

Silas, to return from selling his crop. She also has to take care of her baby,

Ruth. Sarah has fantasies about another man, Tom, and is unsure if she loves

Silas. A white salesman shows up as the sun goes down and tries to sell her a

record player. They make conversation, and as she gets him some water, he

attempts to seduce her. Initially protesting, she leads him to the bedroom, and

they have sex. He leaves the record player with her and says he will try to

return in the morning and convince her husband to buy it.Silas returns, sees

the record player and suspects Sarah has been unfaithful. He drives her from

the house in a rage, whipping her as she goes. Silas hates white people and has

worked ten years to own his farm free and clear. He is livid that Sarah has

slept with a white man, and when the white salesman returns in the morning, he

first whips and then shoots him. As Silas protests that he does not want to

die, but must because he can never be free in a white man's world, Sarah takes

Ruth and runs into the hills, where she watches Silas have a gunfight with the

white mob that comes to get him. He dies when they burn the house down around

him, but he does not make a sound as it collapses on him.

Fire and Cloud

"Fire and Cloud" follows a

preacher, Taylor, as he tries to save his people from a wave of starvation.

Denied food aid by the white authorities, Taylor must return empty-handed to

his church. There he finds a tricky problem. He has been talking about marching

in a demonstration with communists, and they have come to visit him in one

room. In another room, the mayor and the police chief have arrived to talk to

him. Taylor has a history with the mayor, who has done him favors in exchange

for his securing peace and order among the black community. However, if the mayor

finds out about the communists, Taylor will be in trouble. First Taylor talks

to the communists, who try to convince him to further commit to marching by

adding his name to the pamphlets they distribute. Taylor gives them only vague

answers. He then talks to the mayor and the sheriff, who try to convince him

not to march. Again, Taylor is unsure of what to do as he feels that adding his

name will threaten not only himself but his community. He successfully gets

both groups out of the church without their paths crossing. Then he talks to

his deacons. One among them, Deacon Smith, has been plotting to depose Taylor

and take over the church.

A car pulls up, and Taylor leaves the

deacons to see who is in the car. Whites beat him and throw him in the back, taking

him out to the woods. There, they whip him and make him recite the Lord's

Prayer, in a move designed to keep him from marching. Taylor must walk back

through a white neighborhood, where a policeman stops him but does not arrest

him. Once home, Taylor realizes that this beating directly connects him to the

suffering of his people, and he tells his son that the march must go on. Seeing

that many in his congregation have also been beaten over the night, Taylor

leads them in the march through town. He realizes that together, the pain of

his being whipped and the strength of the assembled marchers, black and white

people in one crowd, are a sign from God. The whipping is fire, and the crowd

is the cloud of the fire and the cloud God used to lead the Hebrews to the

Promised Land.

Bright and

Morning Star

"Bright and Morning Star"

concerns an old woman, Sue, whose sons are communist party organizers. One son,

Sug, has already been imprisoned for this and does not appear in the story. Sue

waits for the other son, Johnny-Boy, to arrive home when the story begins.

Though she is no longer a Christian, believing instead in a communist vision of

the human struggle, Sue finds herself singing an old hymn as she waits. A white

fellow communist, Reva, the daughter of a major organizer, Lem, stops by to

tell Sue that the sheriff has discovered plans for a meeting at Lem's and that

the comrades must be told or they will be caught. Someone in the group has

become an informer. Reva departs, and Johnny-Boy comes home. Sue feeds him

dinner, and they discuss her mistrust of white fellow-communists. Then, she

sends him out to tell the comrades not to go to Lem's for the meeting.

The sheriff shows up at Sue's looking

for Johnny-Boy. The sheriff threatens Sue, saying that if she does not get him

to talk, she had best bring a sheet to get his body. Sue speaks defiantly to

the sheriff, who slaps her around but starts to leave. Then Sue shouts after

him from the door, and he returns, this time beating her badly. In her weakened

state, she reveals the comrades' names to Booker, a white communist who is

actually the sheriff's informer. Sue realizes that she is the only one left who

can save the comrades, and she dedicates herself completely to this task.

Remembering the sheriff's words, she takes a white sheet and wraps a gun in it.

She goes through the woods until she finds the sheriff, who has caught

Johnny-Boy. The sheriff tortures Johnny-Boy before her eyes, but she does not

relent or try to get Johnny-Boy to give up. Then Booker shows up, and she

shoots him through the sheet. The sheriff's men shoot first Johnny-Boy and then

Sue dead. As she lies on the ground, she realizes she has fulfilled her purpose

in life.

Literary

significance and criticism

The stories won high critical praise;

what one critic had to say of them is characteristic: "Uncle Tom's

Children has its full share of violence and brutality; violent deaths occur in

three stories and the mob goes to work in all four. Violence has long been an

important element in fiction about Negroes, just as it is in their life. But

where Julia Peterkin in her pastorals and Roark Bradford in his levee farces

show violence to be the reaction of primitives unadjusted to modern

civilization, Richard Wright shows it as the way in which civilization keeps

the Negro in his place. And he knows what he is writing about.

The Concubine by Elechi Amadi

024 : LITERATRURE IN ENGLISH

NOVELS

INTRODUCTION

The work you are about to read, “Concubine” was written by Elechi Amadi, a Nigerian writer.

The work you are about to read, “Concubine” was written by Elechi Amadi, a Nigerian writer.

In this summary, you will read about a girl named Ihuoma; the

most beautiful girl in the village of Omokachi, even though she is from Omigwe.

She got married to Emenike, but later Emenike was killed by his friend, Madume,

over a piece of land, and more for the business of Ihuoma. Ihuoma as been the

major character in this book/work is married to the sea-king who does not want

her get marry to any man on earth.

No one in the village is ready to believe that the most beautiful, the hardest working and the most elegantly behaved woman in the village, Ihuoma, isn’t just an ordinary woman. Two men have already been killed by the wrath of her husband, a god of the sea. When the best dibia ( medicine man) in the village tells a young man in love with and inspiring to marry Ihuoma the truth of the matter, the young man vows that if he married Ihuoma for only a day and then died, his soul would travel away happily. It happens that he is struck just a little before marrying Ihuoma proving that she is indeed a goddess and therefore a god’s concubine.

I. AUTHOR’S AUTO-BIOGRAPHY

Elechi Amadi who writes with speed and sharpness and exhilaration…A lovely and dignified picture of a society not only still ruled by the gods; the Author of “Concubine”, was born in 1934, in the of Aluu, near Port Harcourt in Eastern Nigeria.

He attended the Government College, Umuahia. He also graduated from the University College where he graduated with a Degree in Physics and Mathematics.

Amadi has written many African novels including the “Slave (AWS 210), and Isiburu, a verse play”. He also authored the book Ethnics in Nigerian Culture (Hernemann). Elechi has served the Nigerian Army, the Former 3rd Marine Commandos and later became the Head of the Ministry of Education.

Many people who have this book, “Concubine” have praised it for its simplicity and it is very easy to be responded. It presented the exact copy of the African Culture “The Village Life”

II. GENERAL SUMMARY OF THE NOVEL (CONCUBINE)

CHAPTER ONE

In this chapter, fear hits emenike as he wonders over so many things, including the death of an old chief. There is a quarreled over a piece of land between Emenike and Madume, as Madume is considered as dishonest land grabber, by Emenike, and Madume threatens to beat Emenike if only he (Emenike) does not desist from his habits. The quarreled between them continued until they got into a fight that led Emenike suffering from a side complain.

CHAPTER TWO

Like some guys who have no time as to their prospects in life, Madume was now in his thirties and had not achieved anything in life. His huts were small, he had very small yam farm, and even never cared for having more houses only because he feared thatching them when ever it’s rainy season.

Wolu, his wife who had bore four children (girls) for him was annoyed with him about his weakness in doing things to cater to his children. He only cares to talk about his children’s dowry that would be paid by their grooms to be. He feels that he’s going to make more monies from their prices.

Madume has fallen sick, a day after the fight between him and Emenike. Nwokekoro has come to visit him-that which is a sign of reassurance for him.

CHAPTER THREE

The chapter beings with the gradual recovery of Emenike, as he and his kids are found in the reception hall roasting and eating maize. The family of him is now happy over his recovery.

CHAPTER FOUR

The scene is in Omokachi, a small village comprising eleven family groups. It was located by Aliji and Omigwe. It takes only a brave man to leave Aliji to go to Omokachi. Chiolu was another nearby village to Omokachi; people from the both villages met most often and worship together, to Mini Wekwu. People worship, the god that controls smallpox.

During the times, people dared not to be kind, using being is that the gods change at any time in the form of human beings to ask for gesture, and if denied, that person would contract the disease. Ihuoma’s husband Emenike is dead as the result of a lock-chest, even though people believed it was as the result of the fight between him and Madume.

CHAPTER FIVE

It is market day, as Ihuoma sits and witnesses her romping about forgetting about the death of their father. Wolu comes to visit Ihuoma at her house with the clear mind that Ihuoma was tired of people coming to sympathize with her.

Wolu tried to converse with Ihuoma, she (Ihuoma) cried a lot for every time she is been reminded. Ihuoma accuses Wolu about the death of her husband, blaming it on her (Wolu) husband. Ihuoma cried over and over and again. She thought about here husband. Her mother Okachi wondered over the situation too. They wondered and wondered as Ekwueme comes to visit the bereaved family.

CHAPTER SIX

The chapter opens with Ekwueme going back to his home, after few hours of visitation to the ber3eaved family. He and Wakiri are discussing on how to design and sing a song in honor of Emenike, Ihuoma’s husband.

One month after Emenike’s death, people of the village gathered themselves one evening to have some entertainment/relaxation. Men took-up women. Mman who happened to be one of the best drummers in the area is found carrying his normal activities of beating drum. It was at this that the song composed in honor of Emenike;

Do you know that Emenike is dead?

Eh – Eh – Eh,

We fear the big wide world

Eh – Eh – Eh,

Do not plan for morrow,

Eh – Eh – Eh …was sung.

This song touched Ihuoma, and she cried in a very loud voice, remembering and missing her late husband; the one she once loved. The ghost of her husband appeared to her and asked her for food and later vanished at the she had gone to prepare the food.

CHAPTER SEVEN

After a year of sorrow, when the rain had come again – blooming the farms, the feast of Emenike was set for the period right after the yam festival, when there would be more yams to feed those who attend the rites. Nnadi; Ihuoma’s brother – in – law had dried enough of meat for the festival; there were goats, chickens and much food for the feast. The place and all is now prepared for the feast. The old ladies were welcomed with dried meat, palm oil sauce and pepper, while the people arrive, and then entered two ladies with sharp knives in their hands. They rushed in the place with a loud voice informing the people about an attack that has been fought by the gods, on their behalf.

Ihuoma can now dress as the feast has come to an end. She dresses for the first time since after the death of her husband.

CHAPTER EIGHT

The worries and feast had all gone. Ihuoma had now come to realize that she needs to cater to her children that her husband has left behind. She puts all other things behind her and became focused as she regains her structure and beauty. Men again chased after her. While she goes to visit her parents, they tell her about the love that Ekwueme has for her, and she down plays it.

CHAPTER NINE

The rainy season is now here, Ihuoma is in worry as to her thatches conditions, as Nnadi; Emenike’s brother discusses with his wife to help Ihuoma fix her thatches the next day.

The next morning, Nnadi, Emenike and Wakiri got set at Ihuoma to help her in the process. As they build the thatches, they are found discussing on how many people in the town felt that Ekwueme’s mother would not have bore any other child again after she had bore Ekwueme and his little sister at which time twelve years have passed without her getting any sign of pregnancy. By the time she got pregnant, nearly every one felt that it was a disease until Ndalu, the expert of child birth announced that she was pregnant after which time she (Ekwueme's Mother) gave birth to a strong boy.

CHAPTER TEN

Emenike’s death brought confusion into the mind of Madume, but later over came it, saying that Emenike’s death was somehow supported by the gods. He believed that he now had a second chance of getting Ihuoma, but Ihuoma no time for him; she didn’t even speak to him when ever they met. Madume had gone to his wife to discuss the matter with her, about his love for Ihuoma, and his intention to marry her. But the pronouncements shocked his wife.

Madume later left and went to the street where he met Ihuoma. He tried speaking to her and she only replied with out any further comment. At Ihuoma’s house, Madume saw the grave of the late Emenike and he became afraid to the extent he had to cut his toe. He later left her and went to his house where Anyika had come to visit him, he explains to Anyika about the situation/his cut, and Anyika tells him that this was as the result of the anger of Emenike and his ancestors, therefore, he Madume is to make a sacrifice to the gods before he can be set free.

CHAPTER ELEVEN

This chapter opens with Nnenda, Ihuoma's neighbor and friends conversing with one another about how their children and husbands had been sick for the past times. Nnenda goes to Ihuoma asking her to go into the bush together. While on their way, Nnenda tells Ihuoma that Ekwueme pleads with her, but Ihuoma had no time for what was been said by her friend

CHAPTER TWELVE

The night has fallen and Madume sends Wolu to fetch water for him to wash his hands. As he washes his hands, he feels that no spirit would anything to him only because he had done the sacrifice.

Ihuoma is found picking plantain on the land which her husband, Emenike was killed for after Madume had beaten him for that land. Madume appears on the scene and tried stopping her from picking anything from the land, reason being, he claimed that the land was his, even though the elders had investigated that matter long ago when emenike was alive, and the land was Emenike as the elders quoted. But yet still, Madume claimed the land to be his. He asked her to compromise the case or else he takes everything away form her, but she refused, and jumped on her to fight when people from the near by village came to part them, and Ihuoma left the place, leaving him there.

While there alone, Madume decide to pick some plantain when a cobra spat in his eyes, and the people rushed him Anyika and told them that this the cause of some extra powers that Madume needs to make a serious sacrifice before he can be freed from this trouble.

With they did, Madume still became blind, he even grew more problematic as his wife suffers from it and later decide to leave to go to her parents to come back the next morning.

The sound of cries shocked the entire town from the home Madume, as the people come around to find out what was the cause. To their outmost surprise, Madume is found dead, his body is an abomination to the town; therefore, he needs to be thrown into Minita; the place where rejected bodies were to be carried.

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

It is an Eke day, Ihuoma is found sitting at her reception hall crackling palm nuts when she saw Wolu coming her direction and she thought about the way Madume was killed – so bad. Nnenda had come to visit her that day, as Ekwueme comes to visit also, and he was asked to come the next day.

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

Wakiri, Nnadi, Mgbachi, Ihuoma and the other are eating as they get prepare for the job to thatch Ihuoma's house. After the job, everyone went his way, as Ihuoma and Ekwueme went to her house. At her house, Ekwueme tells her that he really loves her but she aggressively responded him. As the result, Ekwueme woke up angrily and decided to leave the place, while on his way, she ran behind him asking him to come back so that they can better talk about it. She told him that he is a married man, he needs to look after his wife and keep her.

The whole place is now dark as Ekwueme went home and rocked at his parents’ window to open the door for him. His parents are now discussing on how to get set to go and pay Ahurole's dowry, as they also discourage him form Ihuoma.

CHAPTER FIFTEEN

Ahurole and her best friend Titi are fetch water together as they talk about Ahurole sleeping in bed with someone, most especially man, and she is advice to start practicing it. Wonuma, Ahurole's mother tells her to get prepare to work the next day, and to know how to compose her self as they get ready to receive their guests.

Right after the advice, Ahurole and her brother Ikezam are found quarreling over a piece of soup she had cooked for them. This led to Ahurole crying because her brother had insulted her, she claimed.

When both sides (Ekwueme and Ahurole) parents put them together, they were by then five (5) and eight (8) respectively, Ahurole's parents were happy for Ekwueme to get marry to their daughter.

CHAPTER SIXTEEN

Ekwueme is not happy over the idea of getting married to Ahurole. He told his father about this, he had planned to go to his animal trap the next morning while his parents were getting prepared for their departure. His recent behaviors worried his mother a lot, and she even thought about Ihuoma, saying was the one stealing her son heart from the person they want him to marry. She and her husband told Ekwueme about the dangers involved in getting married to Ihuoma; they told him it would bring them disgrace.

As the result of this, Ekwueme's parents sent words to Ahurole's parents asking them to postpone the date to another date.

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN

With tiredness, Ihuoma returns from Omokachi where she had gone to visit her parents. She discusses with Nnadi about her family in Omokachi as Nnadi tells her how Ekwueme had gone looking for her while she was not there.

Nnadi is gone as Ekwueme and his father Wigwe, come to visit Ihuoma that night, as she tells them that the night was too dark for them to come and visit her. Wigwe tells her that he had come to find out about the relationship between her and his son, as he talks, Nnadi arrives. Nnadi had come fearing that it was some one else who had come to either harm Ihuoma or to visit her. Because of the visit of Nnadi, Wigwe changes his words by saying, Ihuoma, I have to ask you to marry my son, but knowing the situation very well, Ihuoma refused his gesture and turned it down. Ekwueme and his father woke up and left for home with all the Vaxstation in him, even though he was not vexed with Ihuoma, but his father.

The next morning, Ekwueme woke up and went into the bush and spend the whole day there, as his mother worried about his where about. Late in the evening, he returned with the biggest animal he had ever killed in his life. They fixed the meat, dried some and he even took some and gave it to Ihuoma's son that which Ihuoma took and wanted to throw away.

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN

The next Eke has come, Wigwe, Mmam, Wakiri and Ekwueme are found making their way Omigwe, to talk about Ahurole, the girl whom Ekwueme's parents want him to marry. There is no sign of anxiety in the eyes of Ekwueme; he seems to be sad as they are on their way. But while in Omigwe, they were treated as if they were at home. Ekwueme felt about Ahurole in many different negative ways, but at the end, he finally bowed to it.

They talk has begun, as Ahurole shows no sign of maturity even in the presence of Ekwueme, the man she is about to get marry to. They continued the ceremony to Omokachi, the home of Ekwueme, where he had so many girls waiting to see him and his girl. But while in Omokachi, the girls tell Ahurole to be a girl who is strong, because there is no lazy girl in their place, Omokachi.

The ceremony is now over, as Ihuoma congratulates Ahurole about the ways in which she had married Ekwueme. At least Ihuoma now believes that she is free as the result of the wedding.

CHAPTER NINETEEM

Things are now normal in Ihuoma's life once again, she no longer worries over any thing. She and her kids play during the night at most times, she thinks that Ekwueme does not think about her any longer as she her self does not think about Ekwueme any longer.

CHAPTER TWENTY

What a great thing? What should have been negotiated for with in a period of one year has now been done in a period of six months. Ahurole whose negotiation should have been done with in a year’s time in order for things to go on straight was now done in a period of ½ a year. She is now found in the house of Ekwueme, six months after the marriage ceremony.

Ihuoma's friendly actions and kindness towards Ahurole had left Ekwueme with no alternative but to feel reluctant about her. Even though Ekwueme is now a married man, but his behaviors still remain the same. He still eats the overnight foo-foo from his mother, he still goes in to the bush to see his trap the usual times he had been going, he still wrestle as like the times when he was small when he was a lazy boy. He even makes confusion with his wife over the kind of food to cook for them that day – that which actually hurt Ahurole and led her to cry.

CHAPTER TWENTY ONE

At the home of Ekwueme and Ahurole, there was some quarrel, Emenike now feels that Ahurole needs to be with an old man to pet her at all times. He is found angry with his wife most often, his parents had advice him, but to no avail. There was no water ready for his bath most often, he had no sleep at all any longer, and he blamed all these to the childhood marriage his parents had carried on. With all these on going, they got in to fight on some occasions and she had to escape to go else where.

CHAPTER TWENTY TWO

The whole village is up side down, every one is doing his/her own thing, the sun is going down Chiolu, every one is found in the market, as Ihuoma and Ekwueme are seen transacting business as they discuss Ahurole and her times being with Ekwueme. Ekwueme still has that love for Ihuoma, and is still pestering her, but she has no time for that. She even planned to report the matter to his mother. She even told Nnadi to advice him on the matter.

CHAPTER TWENTY THREE

Ahurole's goat that was given to her by her mother as a present on her wedding, is no where to be found, it has getting missing, and it was found in Ihuoma's compound. She had come to look for her goat in Ihuoma's compound when Ekwueme saw her coming out and he accused her of pestering around with her, and it made him angry.

Few times after, Ahurole set and left for her mother’s place, leaving Ekwueme all alone. At her mother’s place, she was informed of a medicine to be made to tract down Ekwueme, and she carried it alone with her back to Omokachi.

Ekwueme has now fallen sick as his entire body is now unable to do anything. His conditions had grown worst; he is no longer in good condition. His people worried about it, as he lies down.

CHAPTER TWENTY FIVE – THIRTY

Ekwe as he is commonly called, Ekwueme has escaped from the house as his sickness intensifies. His parents have given up on him, but have gone to look after him as to his location. All the best medications were given him up to this time but to no avail.

Ekwueme's situation has full the minds of every one, every body in the village are now concerned and worried about him. He waste every food that comes before him, he does not want to see any one before. He only talks with Ihuoma as he tells her that his parents; the stupid fools are the ones embarrassing him. In his mad state of mined, he tells Ihuoma that he can’t do with out her, and thus he wants to marry her. He tells her that he loves her even more than before.

The recent pronouncement of Ekwueme shocked every one, the bride price of Ahurole is to be returned to her parents, and the parents of Ekwueme made the proposal to Ihuoma's parents, and her parents were happy about it.

But before the new marriage, Ekwueme's parents have been warned to check as to whether there was any benevolent spirits behind what’s happening to their son, that indeed they did. When they went to find out, they found out that Ihuoma was belonging to the sea-king who had married for some years back, and he was angry with any man who comes across her, thus leading to that man’s death.

Now that the secret of Ihuoma is out, every thing is up side down, she is troubled by the world, she fights and later felt to the ground, after which time Ekwueme died.

III. DISCUSSION OF MAJOR THEMES

The major themes here are:

A. Making love with the most beautiful girl in your surrounding: when ever there is a girl in your community that seems to more beautiful than the other girls in that place, be careful with that person, you don’t know what is making that person like that, most especially when person is hard to be dealt with, hard to agree to the love of people.

B. The power of the sea-king: as it is been said, behind every thing, there is a certain kind of power, so too was it in the book “Concubine”. Ihuoma who happens to be the concubine had a sea-king behind her that would kill any man who follows her.

C. The believe in Supernatural Powers: in our African Culture, we believe in supernatural powers. We believe that nothing can happen on its own, unless there is some kind of power that is responsible for it.

D. Reasons for some of the minor conflicts we have in our societies today: there are so many reasons why we have many minor conflicts in our world of today. Some of those reasons would be land problem, the fight over nature, the fight over woman/man, etc.

IV. DISCUSSION OF CONFLICTS

A. The conflict between Emenike and Madume, this lead to the death of Emenike. During a fight that occurred between Emenike and Madume, when Emenike developed chest-lock, it led to Emenike’s death.

B. The conflict between Ihuoma and Madume, this conflict also led to the death of Madume, after he had hit Ihuoma, a cobra spat into his eyes.

C. There is an internal conflict in the mind of Madume after the death of Emenike. He worries about it, he worried over his life.

D. Another conflict arose when Emenike had the desire to follow Ihuoma. There was a conflict him, his mother, father, Ahurole and even with Ihuoma.

E. Ihuoma's conflict started when she could no longer understand her self, when she felt that all was over, most especially when her husband died.

V. THE ROLE OF SUPERNATURAL POWERS IN AFRICAN DAILY LIFE.

Supernatural Powers as it is well known in our African plays a major role in our daily activities. Every thing we do in Africa has something to do with culture. We believe in Supernatural Powers to the extend that if a woman is even pregnant, we say that there is a special kind of power (from the ancestors) that is responsible for that. When there is no rain, we say the gods are angry. These are things and happening of nature that we believe in to link it to the gods/ancestors. We respect it to the extend that we are even afraid of it. These are all things that do not actually exist, but it does in their communities and societies in which they all live.

VI. WHO ARE THE CONCUBINES?

A. IHUOMA: is the most beautiful girl in the village of Omigwe. She had an ant-hill complexion. Her body was smooth that any who sees her for the first time falls in love with her. She got marry to Emenike who was a good wrestler.

B. HER SUITORS

1. Madume, he was the first suitor of Ihuoma. He was angry why Emenike got marry to her only because he had decided to marry her. With this, he got mad to the extent that he even went into a fight with Emenike after which time Emenike died as the result of the pain put into his body by Madume.

2. Ekwueme was the one who had the desire to marry Ihuoma after the death of her husband; Emenike. Ekwueme, even though he had the desire marry Ihuoma, even made a proposal to her, but she down played his request. His parent had planned for him to marry Ahurole instead of Ihuoma.

VII. FACTORS RESPONSIBLE FOR THE CONFLICT BETWEEN MADUME AND EMENIKE

Madume, as is known in the novel, is known to be a person who loves quarrelling a lot. The conflict him and Emenike arose over a piece of land that the both of them claimed to have. Madume is considered as dishonest land grabber, by Emenike. As the result of this, the both of them fought for a while throwing one another aside, from place to place. The fight led to Emenike’s side developing a severe pain that made him sick. Worst of all, Emenike taken Ihuoma from Madume caused the conflict to intensify.

VIII. HOW IS THE SEA KING RESPONSIBLE FOR THE CALAMITIES THAT BEFEL

A. EMENIKE: the sea-king was responsible for the death of Emenike because, at the time Emenike and Madume fought, even though Madume hit Emenike, but the hit would not have Emenike to dies if only he did not love to Ihuoma, the goddess of the sea.

B. MADUME: as for Madume, his death was cleared. It was cleared that he was killed by certain power of the sea. Prior to his death, Madume was sprayed by a cobra in his eyes after he had harmed Ihuoma for several times. All the medications were applied, but to no avail. He was even told by Anyika that his condition was caused by powers from the outside world.

C. EKWE: has fallen sick, no one knows whether the medicine his wife brought from Omigwe was the one responsible for his sickness or not, or it was the sea-king responsible for it. All they believe was that he got his sickness from the bush where he had gone to make his trap, from the dirty waters that led to ratchets and itches coming on his skin. The sea-king had made him like that because he had continued troubling Ihuoma.

IX. DESCRIPTION OF MAJOR CHARACTERS AND THEIR ROLES

A. Ihuoma, a beautiful young widow, has the admiration of the entire community in which she lives, and especially of the hunter Ekwueme. However, their passion is fated, and jealousy, a love potion and the closeness of the spirit world, lift this simple Nigerian tale onto a tragic plane.

B. Emenike, the husband of Ihuoma, who was killed as the result of a chest lock, after a fight between him and Madume.

C. Madume, the husband of Wolu. He was killed as the result of a cobra spiting into his face. He loves quarrel, he was a lazy man who achieved nothing while he was young. He was spectacular wrestler.

D. Ekwueme, a villager who wanted Ihuoma but rather failed. He had Ahurole as his girl friend whom he later married.

E. Nnadi, the brother in law to Ihuoma who aided her when her husband was dead. He watched over Ihuoma at all times.

F. Ahurole, the wife of Ekwueme. She was an Omigwe woman who was very beautiful.

G. Wonuma, Ahurole's mother

H. Wagbara, Ahurole's father.

I. Nnenda, Ihuoma's neighbor.

X. CRITICAL ANALYSIS OF NOVEL ( PERSONAL IMPRESSION)

This novel is very easy to be read, understood any analyzed. We feel that Ihuoma, even though it was because of her that Emenike, Madume and Ekwueme got killed and crazy, but yet still one way or the other, she can’t be held liable for that, but rather they should be held responsible for their own situation, most especially Madume and Ekwueme.

Let not the cultural be taken lightly, the supernatural powers be taken for granted.

CONCLUSION

Don’t learn to intrude into other people’s business and never learn to follow others’ women, and never see any beautiful or handsome woman or man in you community and just feel that all is well with that person, some of them might in so many things. Be your self, watch your steps in life and don’t be an efulefu.

RECOMMENDATION

We recommend that these African novels be treated in our school with seriousness, not for joke, as compared to the European ones.

Houseboy by Ferdinand Oyono

024 : LITERATURE IN ENGLISH

NOVELS

Ferdinand Oyono begins his haunting tragedy at

the end of a Cameroonian houseboy’s life. “Brother, what are we,” Toundi Onduo

asks as he enjoys his last arki, only minutes before his death, “what are we

blackmen who are called French?” It is a question that echoes throughout the

novel. Houseboy, the story of an African man who from a young age served

white colonizers in his native Cameroun, depicts the plight of Africans who suffered

brutality and subjugation under the boot of colonial authority. It offers a

glimpse into the life of an articulate African, Toundi Onduo, who was at first

intoxicated by the offerings of the French, and determined to assimilate into

their culture, but later realized the hypocrisy of European culture and

despised its rule of his people.

It becomes very clear within the first pages of

the novel that there is a strong undercurrent of Africa’s struggle to maintain

its unique identity, despite European incursion, and emerge from colonial rule.

Oyono uses two major themes to develop his story: Christianity and sexuality

act as the most important agents of European colonial society in his short but

powerful novel. The actions of the white authorities are determined through the

binary between these two divergent forces and their moral inconsistencies are

made plain. The Africans who lived within the Cameroons had little choice but

to struggle on despite the Europeans’ apparent lack of fidelity to their God, their

morals, and themselves.

In many ways, Christianity was the first wave of

the European imperialist invasion. Christian missionaries, spreading the word

of God to African children through sugar cubes and threats of hellfire, stormed

the beaches and made way for the European occupation. Father Gilbert,

though he appears a benevolent fellow, and is adored by Toundi, is an elitist

and patronizing white man, taking the poor black boy from his family eagerly,

and training him to become the perfect specimen of African possibility; “his

masterpiece.” Gilbert goes so far as to show off “his boy” to the other white

colonists, treating him as if he were a pet. Oh, how the other boys in town

envied Toundi’s new clothing and the opportunities made possible through his

acceptance by the whites! Oyono’s use of Christian paternalism clearly displays

the way that Christianity was sold to Africans. Through treats and trinkets,

they drew children in “like throwing corn to chickens,” and with threats of

eternal damnation, they made them stay, not even knowing where or why they had

abandoned their traditional religions. It would seem the young and naive were

the missionaries’ first conquest in Africa. It is made clear by Toundi’s

affection for Gilbert, and the feelings of protection he has within the

Father’s grace. European paternalism is obvious throughout the novel, but it is

made most pointed through Father Gilbert’s death. Killed by a falling branch

while he hurried to retrieve mail from his native land, he is called a martyr.

“I suppose because he met his death in Africa,” Toundi says. A martyr: killed

in action on the front lines of the heathen world, I suppose.

After Father Gilbert’s funeral, Toundi is

changed. “I have died my first death,” Toundi says, as he sees his naivety die

with Father Gilbert. He mourns his adopted father, but through this, he mourns

himself. Here, the story changes and a new chapter begins. Henceforth, Toundi

is made increasingly aware of the hypocritical actions of the French

colonialists. Gilbert’s replacement, Father Vandermayer, is immediately shown

to be a poor representative of both the church and “God’s love.” Early in the

novel, the young men are sent away from his screaming obscenities during a bout

of malaria, and after Gilbert’s death, he offers no words of wisdom or comfort

to the community who is obviously so broken by the passing. With the death of

Father Gilbert, so also dies Toundi’s innocence.

As our protagonist is passed from the church to

the state at the suggestion of Father Vandermeyer, Toundi finds himself within

another realm of European hypocrisy. He becomes the houseboy of the Commandant,

and is witness to the childish egotism and fickleness of his colonial masters.

Throughout the novel, the white settlers appear unhappy, displeased at their

lot in the sad land of the heathens and uncomfortable in the heat of the

African sun. Throughout the novel the reader wonders, if these colonists are so

unhappy, why do they not simply go home? Constantly they complain at the “state

of things” yet remain in the colony, breaking the African’s backs to maintain a

position of authority.

One character, the French agricultural engineer

referred to only as “Sophie’s lover,” gives us one example of how dishonest and

hypocritical the whites can be, especially when controlled by their sexual

appetite. Sophie, the engineer’s black mistress, exclaims her foolhardiness for

not fleeing the man who keeps her around for sex, yet hides her as a secret

from other colonists. The relationship, and the engineer’s attachment to

Sophie, is made more hypocritical when Toundi receives a threat from the

engineer not to have relations with her. The engineer hides his lust for Sophie

from other Europeans, yet he is jealous of her with other Africans. Ultimately,

Sophie acts out her desperate wish and flees to Spanish Guiana, relieving the

engineer of several thousand francs. Angry and ashamed, he accuses Toundi for

the theft of his money and his woman; both items he treats as material

commodities.

The most important display of European hypocrisy

is in the relationship of the Commandant and his wife, referred to only as

“Madame.” The Madame, proclaimed as the most beautiful woman in the region

wastes little time before she begins an affair with Monsieur Moreau, the

director of Dangan’s prison. At first, she hides her relationship. She is a

christian woman and the wife of the highest ranking official in the area.

Soon though, she is overtaken, and begins seeing him almost daily, kissing him

even in the open afternoon sun. When her thinly veiled secret is out, known

seemingly to every African in town, rather than breaking off her relationship

with the director, she becomes rancorous towards her servants, finding fault in

all that they do and projecting her fallibilities onto them for their knowledge

of her secret.

Interestingly, her troubles do not begin until

after an interesting encounter with Toundi. Though previously, the Madame paid

him little to no attention– his heart broken as she gazed upon the garden and

had forgotten he was there– things changed swiftly after their journey to the

market. In response to the incessant cat calls the Madame received but did not

understand during their trip, Toundi explained the locals’ lust for her. “That

is very nice of them,” the Madame responds, but a flicker in her eyes reveals

the transformation that has taken place. In Toundi’s next passage, the Madame

questions him about his job, and then subsequently his love life. While Toundi

doesn’t realize it, the Madame lusts for him, not as a man but as a lover;

merely an object to satisfy herself with. “You only have to look at her eyes

when she talks to you,” Kalisia reveals later. Yet another white colonist

wishes to own an African, both sexually and economically. It is no wonder the

Madame turned to Moreau. “I’d say she couldn’t do without a man for even a

fortnight,” Kalisia explains.

“I thought of all the priests, all the pastors,

all the white men, who come to save our souls and preach love of our

neighbours. Is the white man’s neighbour only other white men?”

Toundi’s sorrowful question speaks to the

injustices of the French colonial policy of assimilation. In francophone

Africa, the colonized were taught that by learning to speak, act, and believe

like a Frenchman, they could indeed become French; as much a citoyen as any man

born beneath le Tour d’Eiffel. This policy was, in the end though, a bold faced

lie. Whether the French believed their lie or not, neither their hearts nor

their country would open to include their colonial subjects. No matter the

rank, education, poise, or beauty of the Africans who wished to assimilate,

they remained lower even than the most unsavory and downtrodden white

Frenchman. No matter what an African could do, he was still black, and could

never overcome the hurdle of acceptance into French culture.

This widespread belief reveals the inherent

racism underlying the entire imperial enterprise. It is prevalent throughout

Oyono’s novel. Even if Africans adopted European ideas and assimilated into

their culture, they still could not be good enough. The one character that

disagrees, Jacques Salvain, the headmaster of the school, makes a scene by

comparing the lack of morals in Cameroun with the lack of morals in Paris. Even

he takes a paternalistic stance though, encouraging Africans that they can be

as good as Europeans, yet judging them by a European model of “good.” The group

of white colonists ask themselves fearful questions as they sit and contemplate

the immigration of “natives” to Paris. “What would happen to civilization?”

The French policy of assimilation can be called

patronizing at its very best. Oyono’s depicts the French treatment of Africans

as if they were animals throughout the novel. Gilbert, as he throws his corn to

the chickens; Toundi, as he felt like a parrot being lured by treats or even as

the “King of the Dogs,” the servant of the Commandant; always the Africans are

emasculated and infantilized. “I am the thing that obeys,” Toundi says,

accepting his fate from a young age. If an African becomes a Frenchman, then,

does he become un chein français? “Who are we blackmen who are called French?”

The question echoes in my heart.

Oyono’s novel is not without hope, though, for

through Toundi, a strong African voice rings through the omnipresent European

racism. This tragedy, like any, gives the protagonist an opportunity to speak

his peace before his time is done. Throughout the novel, there are several ways

that Africans establish and maintain their unique cultural identities despite

the oppression of external imperialistic control. Throughout the novel, Oyono

emphasizes the importance of dress, names, and dialect. Africans are able to

differentiate between even other native Africans by the way they dress, and it

is clear when someone has adopted the ways of the whites, simply by their

outfit. Dialect is another important factor of African identity. Often,

Africans use their native tongue to speak ill against the white man, share secrets,

or communicate in a way that is purely— and solely— “native.” Father

Vandermayer’s broken and incorrect Ndjem leads him “in his innocence” to embark

upon a “sermon full of obscenities.”Whether for fear or for humor, the native

speakers of Ndjem do not correct him. Later, once the village of Dagan learns

of Madame’s infidelity, they shout lewdly at each other in their native

language, calling the Commandant “Ngovina ya ngal a ves zut bisalak a be

metua,” The Commandant whose wife opens her legs in ditches and in cars.

Equally, the French use language as a wedge between the “Master Race” and his

servant. Later in the novel, when Madame’s adultery is discovered, though

Toundi is placed in a position of power in respect to the secret holders, he is

referred to as “Monsieur Toundi”, a title given almost in jealousy. “It

is a bad thing when a white starts being polite to a native,” Toundi’s friends

tell him, for the whites would never allow a “native” to stay in authority for

long.

There is a constant atmosphere of sexual tension

between the native African population and their white colonial rulers. When

Toundi sees the Commandant in the shower and realizes his master has not been

circumcised— an important element in becoming a man in his Cameroonian

tradition— he feels a pang of embarrassment. He is not embarrassed for himself,

though, he is embarrassed for his master and all the other foolish whites in

his land. Toundi suffers his “second death,” and knows in his heart that he

will never be afraid of the Commandant again. Later, when he realizes his

Master’s cuckoldry, he suffers his third. How could he respect a man who acted

without dignity? Toundi’s fate is sealed. He cannot continue as a boy, for he

has become the master in his own mind. Yet he remains in their charge

until the end, “more or less,” for “a river cannot return to its

spring.”

In the end, Toundi’s fate is to suffer a tragic,

yet heroic death. Though he was advised to flee by Kalisia— the reader

screaming internally at Toundi, begging him to depart— he remains. Is it pride?

Is it honor? Is it folly? The truth is not revealed. Inasmuch as he is led like

a lamb to the slaughter, Toundi retains his pride until the end. His humor

never fades. Joking even with the sergeant who was sent to beat him, he laughs,

knowing the short time he has left. Toundi is beaten to within an inch of his

life, in a chapter rife with similes to Christ’s crucifixion, yet he retains

his dignity. “I felt pleased to think that neither the Commandant nor M. Moreau

nor Sophie’s lover,” he says with pride, “nor any other European in Dangan

could have stood up to it like we did.”

Where once the Houseboy had been the servant,

“the thing that obeys,” in his death he had become the storm. Gathering his

last ounce of strength and courage, Toundi flees the hospital, running to

Spanish Guinea as he was once advised. In a clear allusion to Christ, as Toundi

enjoys his last cup of rum with a wink, he says “I am finished… they got me.

Still I’m glad I’m dying well away from where they are.” Even in death, his

spirit could not be contained. “How wretched we are,” he said once as he

watched two fellow Camerounians, beaten to death for a crime they probably had

not commit. Yet, in using the plural pronoun, the reader gets the impression

Toundi refers not only to his black countrymen, it seems he is speaking to all of

humanity. This is echoed on the final page of the novel by Mendim me Tit, the

man ordered to beat Toundi, when with tears in his eyes he says, “poor Toundi…

and all of us.” How wretched we are indeed.

Houseboy by Ferdinand Oyono offers us an

interesting peek into the life of a Camerounian shortly before it declared its

sovereign independence from France. It is not clear exactly when the novel is

supposed to have taken place, but based on the Cameroons unique colonial

history, the reader may assume that it took place during the 1950s. Though it

is a fiction, it provides a strong African voice in a time of great turmoil.

Written in 1956, four years before Cameroun achieved independence, it is a good

representation of the anti-colonialist literature that was prevalent at the

time in both the Cameroons and all of Africa. Cameroun, and its neighbors the

anglophone North and South Cameroons, struggled to find a cohesive Cameroonian

identity. Neither dictated by language, religion, family, or tribe, the three

separate states ultimately united to form the United Republic of Cameroon, a

nation built of negritude and the pride of being a Cameroonian.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)